Load-bearing antique (200 year old) White Oak timbers, the primary structural members for the new…

Dan Kiley’s Sarah Scaife Sculpture Court

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh PA

The elfin behavior of Dan Kiley belies a vast trove of work generated by a complex mix of intuitive design and gridded modernism. Kiley’s oeuvre; both forthright and elegant, rises to the forefront of landscape architecture. This is visible not only through the shear volume of competent projects, some of which are in danger of being lost, but also in the absolute conviction his designs have in furthering the idea of landscape as spatial rooms.

Four years at the office of Olmstead-trained Warren Manning preceded Kiley’s fortuitous two-year stint at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. As Walter Gropius led the architecture department into modernism, Kiley strained against the traditional Beaux-Arts formalism being taught in the landscape school. Working with classmates Garrett Eckbo and James Rose, Kiley assembled the theoretical base of landscape modernism. Design contributions were met by Kiley while Rose and Eckbo did most of the writing.

Dan Kiley knew his trees. He knew scale. He networked. Afternoons meant martinis. Mornings, almost certainly, involved walks, dogs, and New England woods. Kiley’s hyperkinetic energy disguised a body of brooding and calculated work. His intimate offices surrounded themselves with woods. His urban plazas became wetland swamps. Honey locusts, draped in charismatic bark, become sculptures.

This landscape guru abstracted nature. Tadao Ando, an architect who has spent his life perfecting concrete, is still searching for proper sealants and finishes to further abstract his medium. Dan Kiley used natural materials, at their essence a diverse, dynamic, and tactile medium. It is highly likely that had Kiley pursued an architectural career, his deft manipulation of more static building materials would have been nothing short of total mastery.

The vegetation, the hardscapes, even the referential grid and its architecture, become light and shadow; small narrow spaces between horizontal canopies and thick bushy eye-stoppers. The confidence of the trees, the hedges, the ground cover, even the autonomous tendencies of strong architectural materials like granite and marble, disappear and are replaced by a commonality of place-making. This can be attributed to the keen knowledge Kiley had of plant material; its growth and placement. Credit can also be given to the classic and formal composition of allées, bosques, hedgerows, screens and walls that blend architectural matter and plants into one. Yet it is not enough to say that the formal layout of Kiley’s gardens alone made them successful. The life force with which he lived, overlaid upon ballet-like grid formations of well-suited plant material, in their own right elegant, combine to create garden jewels of irreproducible quality and uniqueness.

Kiley spoke of growing up, of “experiencing a space that was predominantly architectural, man-made. We used to chase each other over backyards and over fences through a maze of yards. It had an architectural, structural/spatial quality that was quite mysterious. That has pervaded my life ever since; the feeling of space and release in my work.”(Dean77). Kiley mastered the composition of bounded and architectural spatiality using landscape form. His gardening prose was “aware of a living space moving and changing among the trees; expanding in the fields between the mountains, and growing smaller in the dark woods”.

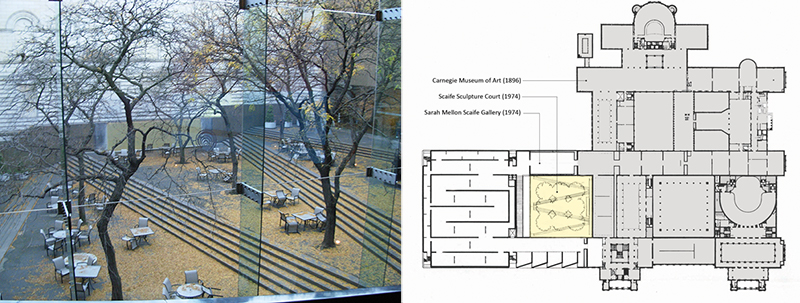

The Sarah Scaife gallery, an addition to the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, PA in 1974 is yet another example of Dan Kiley’s collaborative projects. This one was designed by architect Edward Larrabee Barnes. Interested in sympathetic compositions of light, space, and flow, Barnes created structures that highlight their landscape and site, yet are bold in their own architectural moves. The Scaife Addition, as a large scale art museum project, successfully joins the existing 1895 Longfellow, Alden and Harlow building, with the needs of a museum intent on enlarging its collection. The project extends the existing sandstone beaux-arts gallery west with a minimalist granite-clad housing.

Dan Kiley developed the planting schemes surrounding the new building as well as in the interior sculpture court. Despite the current state of disrepair, the dense Yews in the museum’s parking area, punctuated by flowering Cherry trees, show Kiley’s ability to achieve human scale by adjusting the height of canopies. The untrimmed Yews and hanging Cherry blossoms allow a thin line of site to penetrate their mass. The building is blanketed in a wrapper of mossy green, softening Barnes’ granite walls. The Cherry grid, although ravaged by time, still articulates the difference between the rug-like thickness of the Yews and the sparser, even delicate, Cherry canopy.

The planting strategy continues along the west façade of the building. Higher trees hug the recessed building angles. Yews continue over both surfaces. In bloom, the Cherry trees compete yet are no match for the sculpture court. The building has moments of spatial extension, as in the case with the courtyard’s oversized portal. This gateway allows the gallery to pass overhead while providing a necessary sense of enclosure to the courtyard.

After entering the court underneath the massive plinth of Barnes’ form, one rises on Kiley’s angled terraces; triangular cuts in plan. Kiley transects the orthogonal space into wedges, each with its own light quality, proximity to walls, distinctive honey locust sculpture, and capacity to site various pieces of sculpture. The diagonal stairs overlay the site with angular topography. Kiley’s courtyard is bounded by both new and old walls; granite/glass meets articulated classical style. The triangular platforms present both styles with equal weight. Sol Le Wit astutely adds to the conversation with a multi-colored mural for the grand staircase, best viewed from the north-east corner of the garden.

The Scaife material palette is unusual. Granite curbs mark the boundary between the building and the individual terraces. The surfaces within the triangles are a dark aggregate concrete, with a triangular tip of light aggregate. River stones fill the joint between the two materials. Although the disrepair of the garden illuminates the problem with using aggregate concrete as a quality-invoking material, it is a gutsy and cost-saving choice.

As a modernist garden, the continuation of the Scaife gallery into the garden and vice versa is best articulated in Barnes’ second largest contribution to Kiley’s genius. The tectonics of the meeting of the glass façade wall and the garden plane allows Kiley to utilize several design strategies. Barnes tips his hat to Kiley’s formal abilities, here with a language of architectural detail. The glass mullions of the steel-detailed wall run directly into the ground plane. Kiley continues mullion lines through the terraces as control joints and places trees at their intersection.

The Scaife gallery garden, although a small commission relative to Kiley’s other work, is a remarkable space. This triangulated, ascending courtyard, with its nine tree grid, is an intuitive masterpiece of site specificity, of nature as art, and inspired display of two architects obliterating the demarcations of architecture and landscape.

A Note: The Scaife Sculpture Courtyard is in dangerous disrepair. It is an at-risk cultural asset of the city of Pittsburgh. Although Dan Kiley did also design the lovely downtown Pittsburgh Agnes R. Katz Plaza, for Louise Bourgeois’ sculptures, surely the museum and other members of the design community recognize the superiority and importance of Kiley’s Scaife Sculpture Garden as a gem of modernist landscape design.

WORKS CITED

Brown, Jane Gillette. “Kiley Revisited.” Landscape Architecture. V.88, n.88(1998 Aug): 58-61,86-87,89.

Dan Kiley; Landscape Design in Step with Nature. Process Architecture. 1982 Oct. No 33(entire issue).

Dillon, Dave. “Plain Geometry: in Milwaukee, Dan Kiley’s Cudaby Gardens provides a refined counterpoint to Santiago Calatrava’s sculptural museum.” Landscape Architecture. V.93 n.3(2003 Mar): 56-61.

Eckbo, Daniel U. Kiley, James C. Rose. “Landscape design in the rural environment.” Architectural Record. V.86(Aug. 1939):68-74.

Freed, Stacey. “When Design Compels Movement.” Garden Design. V.5 n.3 (1986 Autumn):65-69.

Herrington, Susan., & Lisa Gelfand. “Rants & Raves: J. Paul Getty Fine Arts Center.” Land Forum. N.2(1999): 205-218.

Herrington, Susan, & Lisa Gelfand. “The Getty: Another Look.” Landscape Architecture. V. 90, n.10 (2000 Oct): 100-107.

Hilderbrand, Gary. The Miller Garden: Icon of Modernism. Washington D.C.: Palace Press International, 1999.\

Imbert, Dorothee. “Working the Land.” Architecture. V.88 n.11(1999 Nov): 69-73.

Karson, Robin. “Conversation with Kiley.” Landscape Architecture. V.76 v.2 (1986 March/April): 50-57.

Kiley, Dan. The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1999.

Kiley, Dan. “A Way With Water.” Landscape Design. N.207(1992 Feb): 33-36.

Saunders, Willism S, editor; with essays by Anita Berrizbeitia. Daniel Urban Kiley: the early gardens. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

This garden still needs attention.